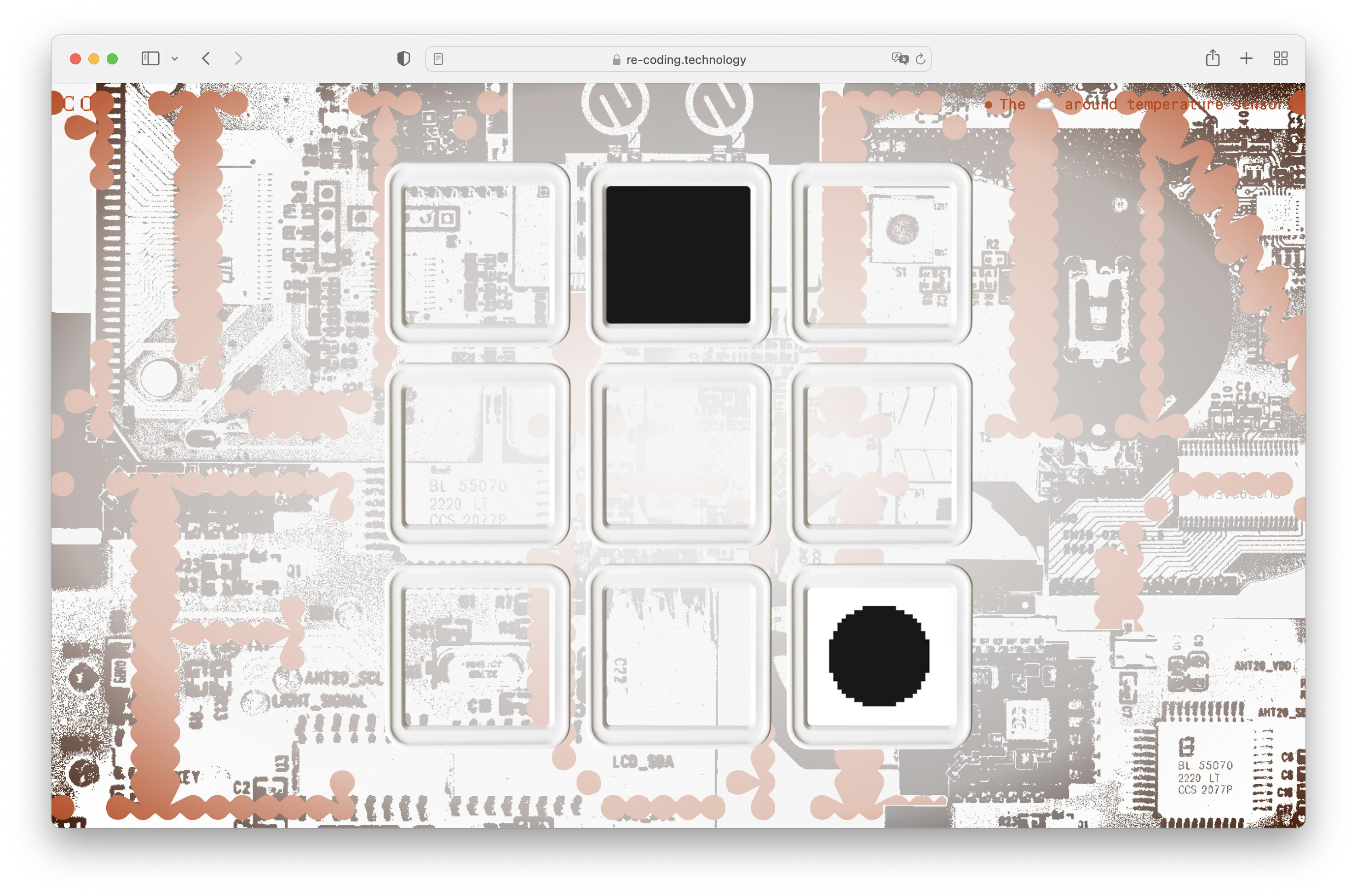

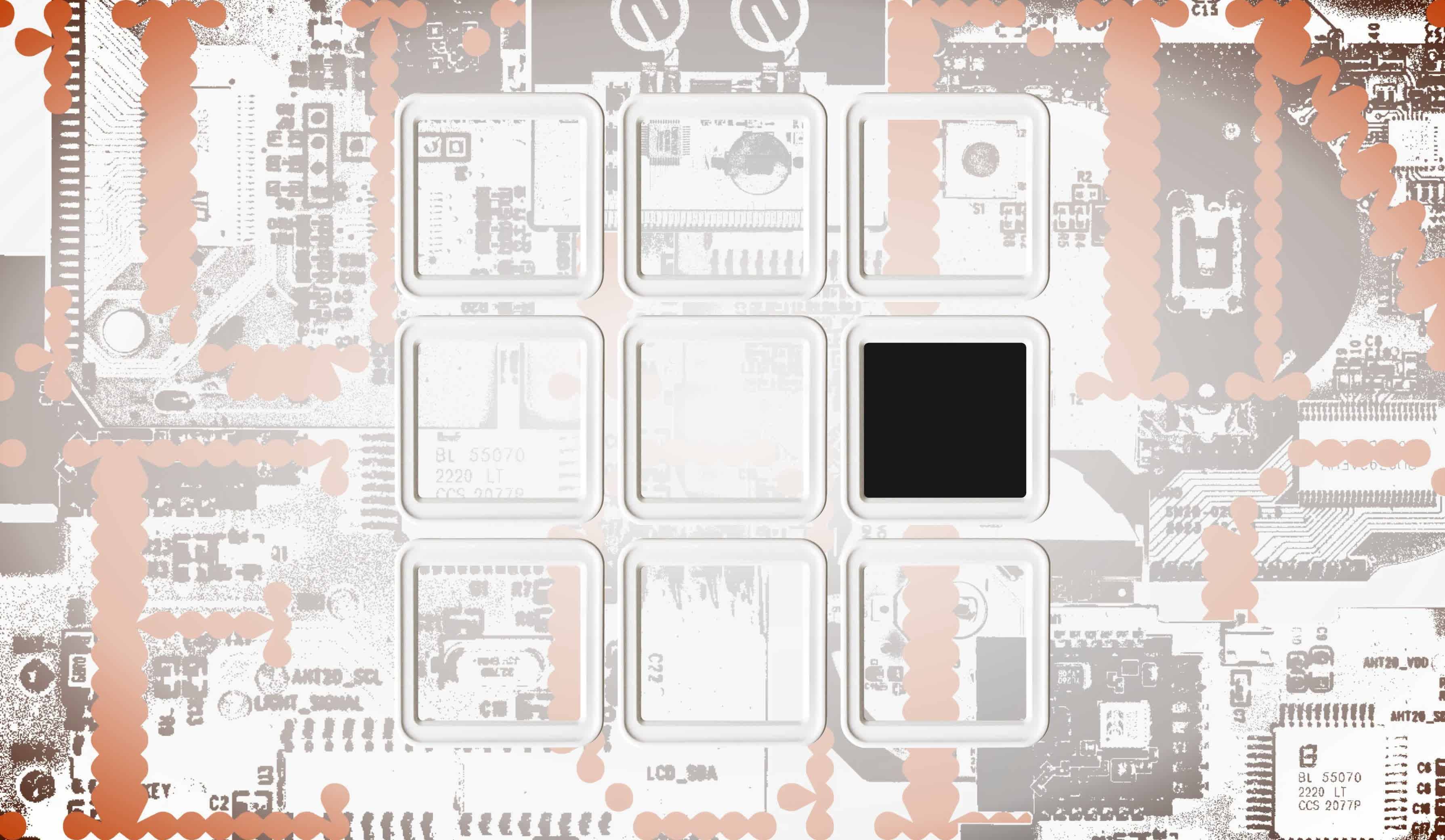

The ☁️ around temperature sensors

In a course I took at the Hochschule für Künste Bremen called Aliexpress Archaeology, our task was to delve into the depths of Aliexpress and find objects that gained our interest. Aliexpress is the consumer shopping platform of the Alibaba Group Holding Limited. It provides a direct link to production facilities, cutting out various middlemen in the supply chain and offering products at low prices.

As I explored the site, my attention was quickly drawn to very affordable smart home products. I was particularly intrigued by a battery-powered temperature sensor advertised as Tuya WIFI Temperature Humidity Sensor Indoor Hygrometer Thermometer Detector Smart Life Remote Control Support Alexa Google Home.[1]

The price of the TH08 temperature sensor was €7.62, which seems rather low for such a technical device. This led me to the following questions:

How can a smart home device, which has quite a few technical features, be offered at such a low price?.

In addition,

What is the purpose of such a cheap device? Who benefits from it?.

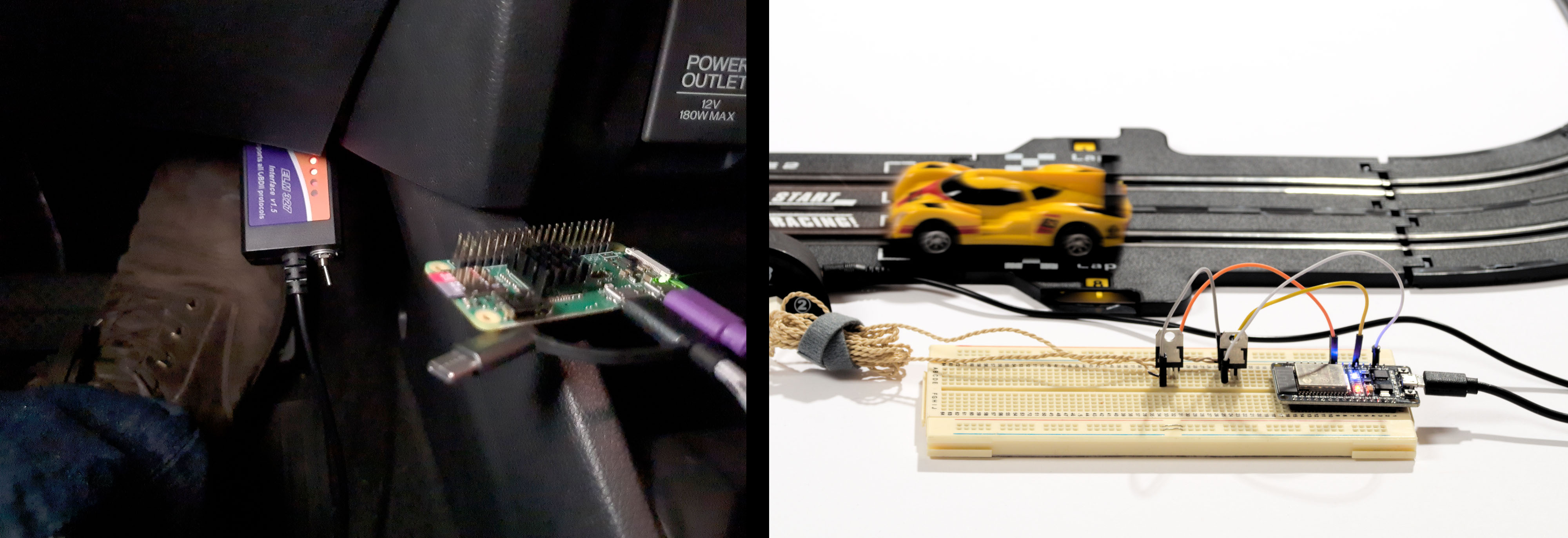

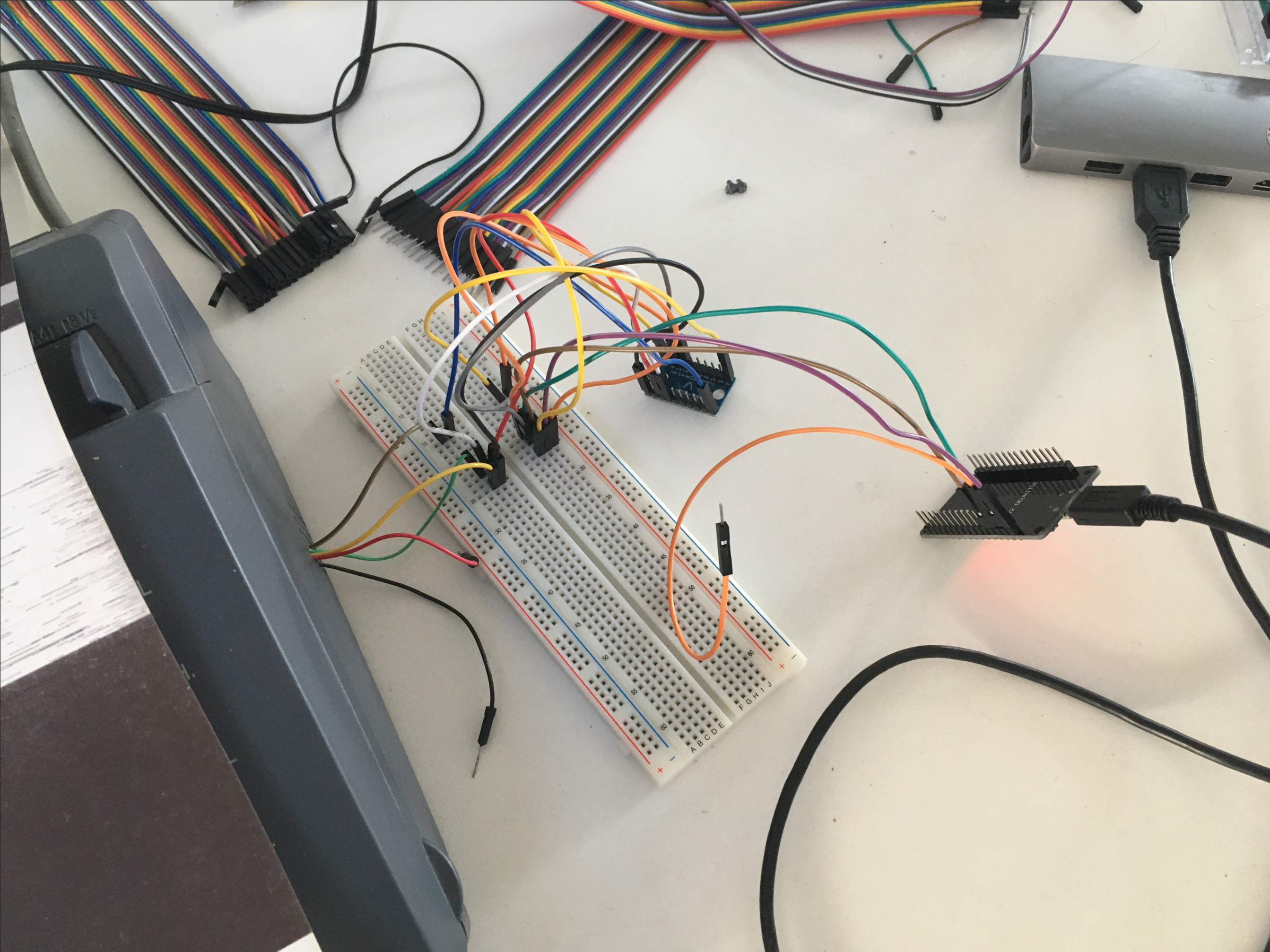

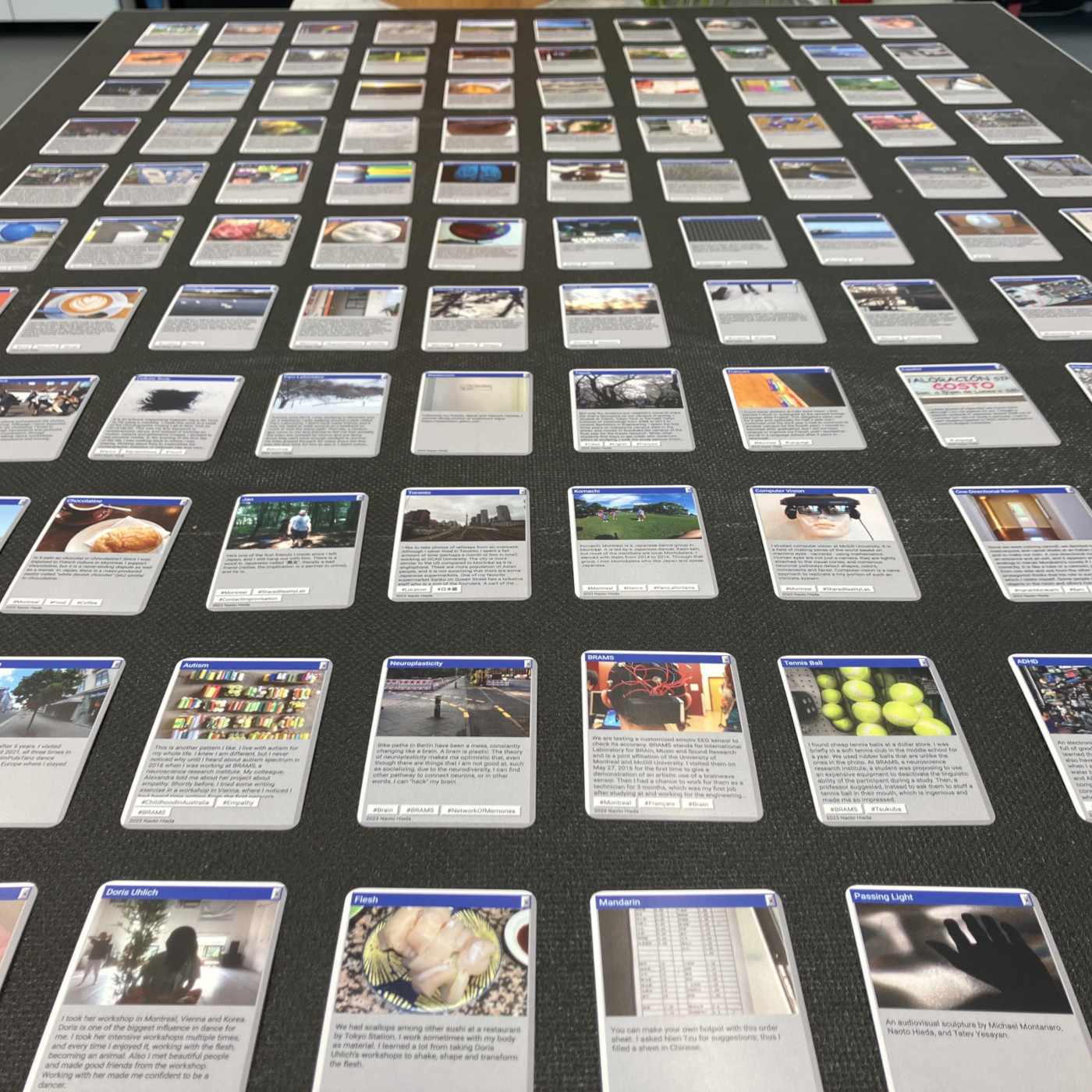

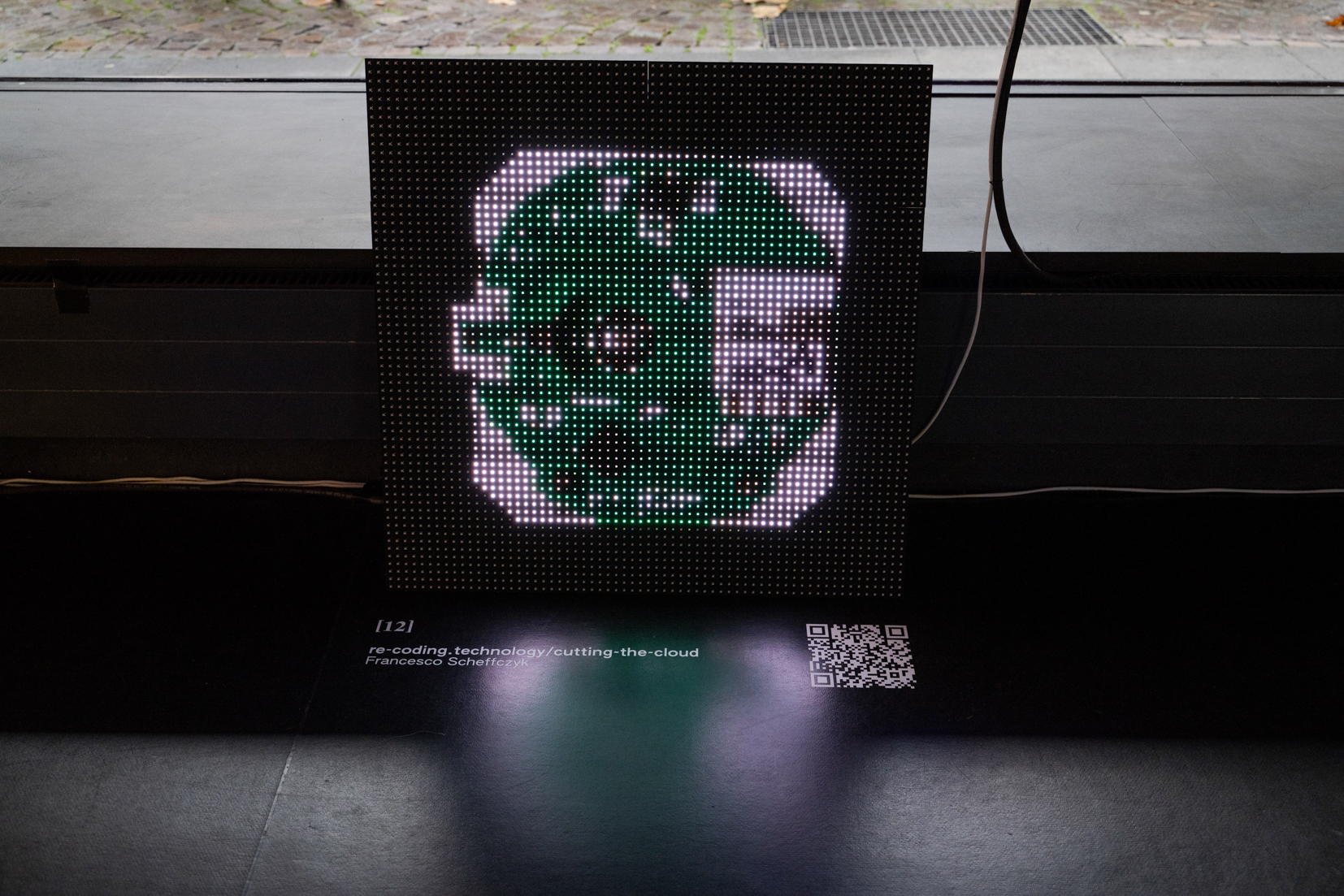

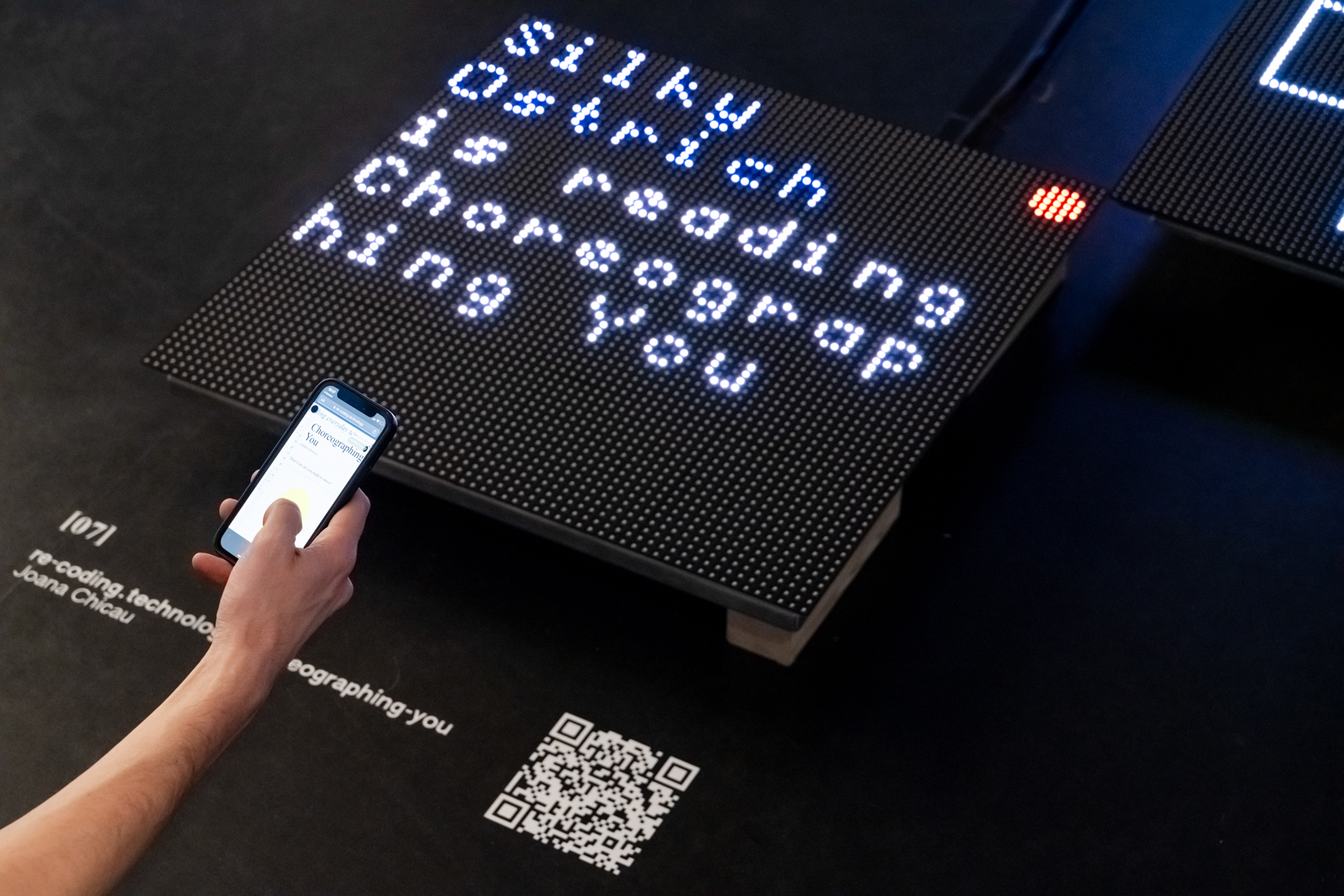

Beyond these questions, I was also intrigued by the device itself. I wanted to see if I could somehow acquire or hack the technical inner workings of it. My original idea was to gain control of the screen and use it to project a visual narrative. Despite my attempts, I was unsuccessful, which you can read more about in the second part of the documentation.

The following chapters are broad areas of research that I stumbled upon while trying to hack the temperature sensors. The research is divided chapters that together try to provide answers to the questions above.

Value of labour

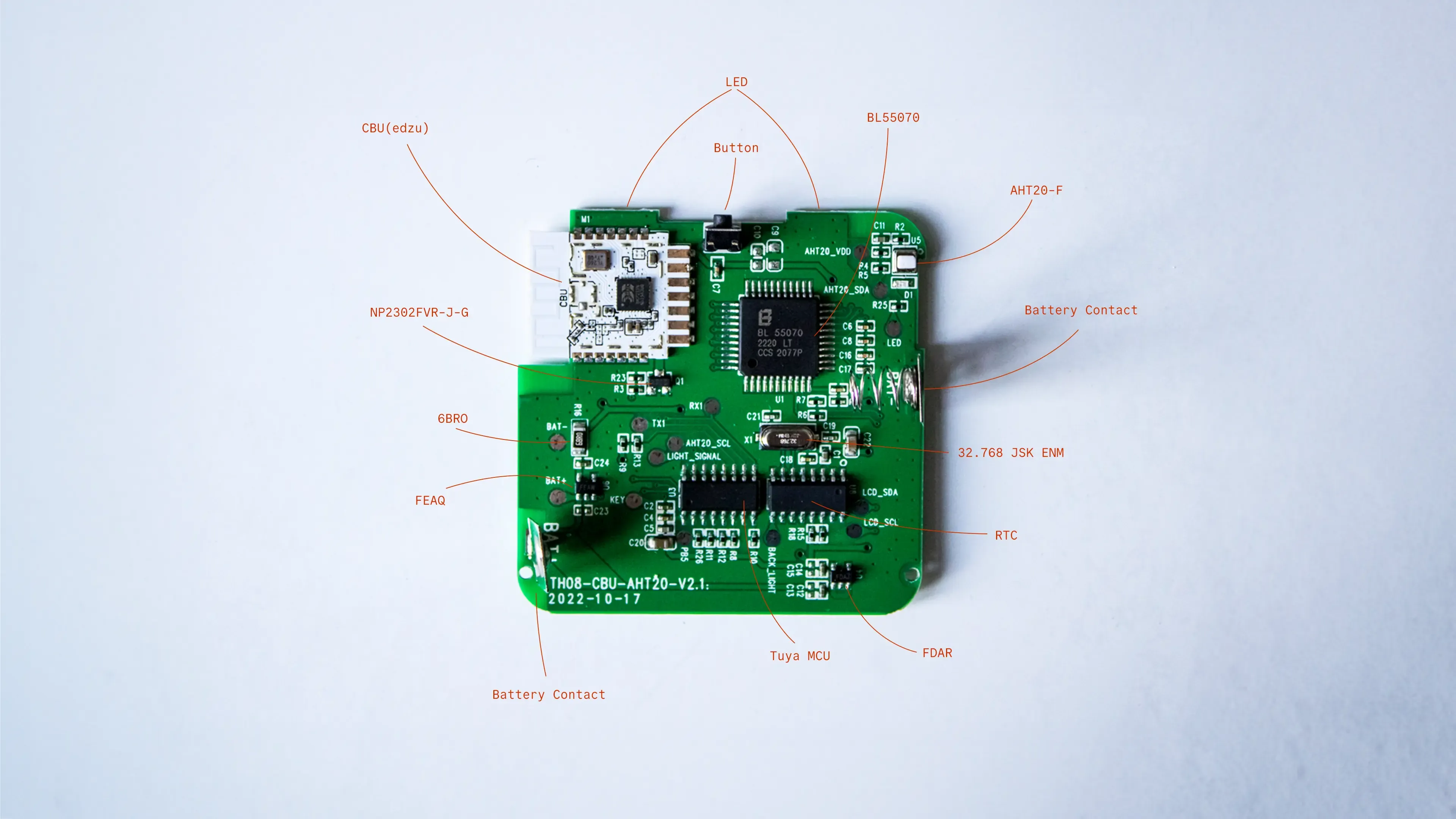

In our current capitalist society, the value of labour is most often expressed in terms of money. To better understand the value of the labour in the TH08 temperature sensor, I tried to backwards engineer the price of the device. I started by looking at the PCB and calculating the price of each component.

I looked up the component prices on the Assembly Parts Lib of JLCPCB. [2] JLCPCB is a commonly used website for making your own PCB designs. As many sellers on Aliexpress and JLCPCB are based in Shenzhen, I thought this would be a good reference point. Two of the chips had the label erased, so the price could not be determined. However, they are probably a TuyaMCU chip and an RTC chip. Some other components have labels, but none could be identified. [3] [4]

Prices from JLCPCB Assembly Parts Lib

| Component | Amount | $ Price | € Price | € Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBU(edzu) | 1 | $3.2121 | 3,05€ | 3,05€ |

| BL55070 | 1 | $0.4865 | 0,46€ | 0,46€ |

| AHT20-F | 1 | $0.6566 | 0,62€ | 0,62€ |

| NP2302FVR-J-G | 1 | $0.0109 | 0,01€ | 0,01€ |

| 32.768 JSK ENM (similar) | 1 | $0.0739 | 0,07€ | 0,07€ |

| LED (similar) | 2 | $0.0101 | 0,01€ | 0,02€ |

| TuyaMCU (unknown) | 1 | ? | ? | ? |

| RTC (unknown) | 1 | ? | ? | ? |

| FDAR voltage regulator (2,8 volts) (unknown) | 1 | ? | ? | ? |

| FEAQ voltage regulator (3,3 volts) (unknown) | 1 | ? | ? | ? |

| 6BRO resistor (unknown) | 1 | ? | ? | ? |

| Button (unknown) | 1 | ? | ? | ? |

| Battery Contacts (unknown) | 2 | ? | ? | ? |

| Price in total | 4,23€ |

Note that this is the price of just some of the components. It does not include the plastic casing, the LCD screen, all the small resistors and capacitors, or the material for the PCB itself. Although this is a very rough estimate, it still gives a good idea of the cost of the materials. Subtracted from the original price of the unit, we are left with:

7,62€ – 4,23€ = 3,39€

From this remaining amount, there are still costs to cover, such as

- Manufacturing costs other than the bill of materials

- Financing costs

- Fulfillment costs

- Fixed costs

- Internal costs

- Packaging costs

- etc.

These are just the so-called COGS (cost of goods). It does not even include the mark-up. [5] [6] Although this is a rough calculation, it is a good starting point for estimating the value of the work that went into making this device.

Aliexpress and Shenzhen

To understand why the device is available at such a price, there are two key aspects to consider. The first is the Aliexpress platform itself, and the second is the production facilities in Shenzhen.

As mentioned above, Aliexpress is Alibaba's consumer shopping portal, known for offering products at low prices. In addition to the fact that manufacturers sell directly on Aliexpress without intermediaries, several other factors contribute to the lower prices. Shipping is subsidised by the Chinese government when using China Post, the national postal service. This encourages sellers to offer free shipping to customers on the platform. In addition, the cost of raw materials and consumables is low for manufacturers, as Chinese government policy ensures that manufacturers can purchase and source their materials at competitive prices. Finally, low labour costs must also be taken into account to keep prices low. [7] [8]

Another important factor is the location of the production facilities in Shenzhen. Shenzhen is a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) designated by the Chinese government to promote economic growth and innovation. As an SEZ, Shenzhen enjoys various tax incentives and relaxed regulatory policies. This has attracted a large number of manufacturers and technology companies to set up operations in the city, resulting in a highly competitive market. The concentration of companies in Shenzhen fosters intense competition among suppliers, which drives down production costs. Aliexpress sellers in Shenzhen can tap into this ecosystem of low-cost manufacturing and use the city's logistics infrastructure for efficient global shipping, ultimately contributing to the platform's ability to deliver low-cost products to consumers around the world. [9] [10]

Dropshipping

Another interesting thing I noticed was that the TH08 temperature sensor and others I bought (you can find a full list in the second part of the documentation) were available outside of Aliexpress. I was able to find several units I bought on Aliexpress on Amazon as well. The pictures, names and descriptions were slightly different, but the real difference was the price. Depending on the device, the price on Amazon was up to 2.8 times higher than on Aliexpress.

| Aliexpress | Amazon |

|---|---|

| TH08 | TH08 |

| TH01 | TH01 |

| KBZ-FR | KBZ-FR |

This calculation only makes sense if you work with the sales prices of Aliexpress, but since my observation the devices have never been out of sale and I have never paid more than the sales price. The high price difference as well as the mismatch in the seller led me to the thesis that the products are sold through dropshipping.

Dropshipping is a business practice where the seller does not keep the products in stock, but instead transmits the customer's orders and shipping details to either the manufacturer, another retailer or a wholesaler who then ships the goods directly to the customer. As a result, the seller does not have to handle the product directly. This practice is very common with products from Aliexpress and explains the price difference between Aliexpress and Amazon, as otherwise the seller would not make a profit. [11] [12]

Another indicator for the dropshipping thesis is the Expo website from Tuya. That platform enables sellers to buy Tuya products in high volumne from certified suppliers. This platform allows sellers to buy Tuya products in bulk from certified suppliers. On this website, it is also possible to buy the TH08 Temperature Sensor that I bought from Aliexpress, even with the ability to customise it.

Proprietary Technology -

TuyaMCU and Tuya Cloud

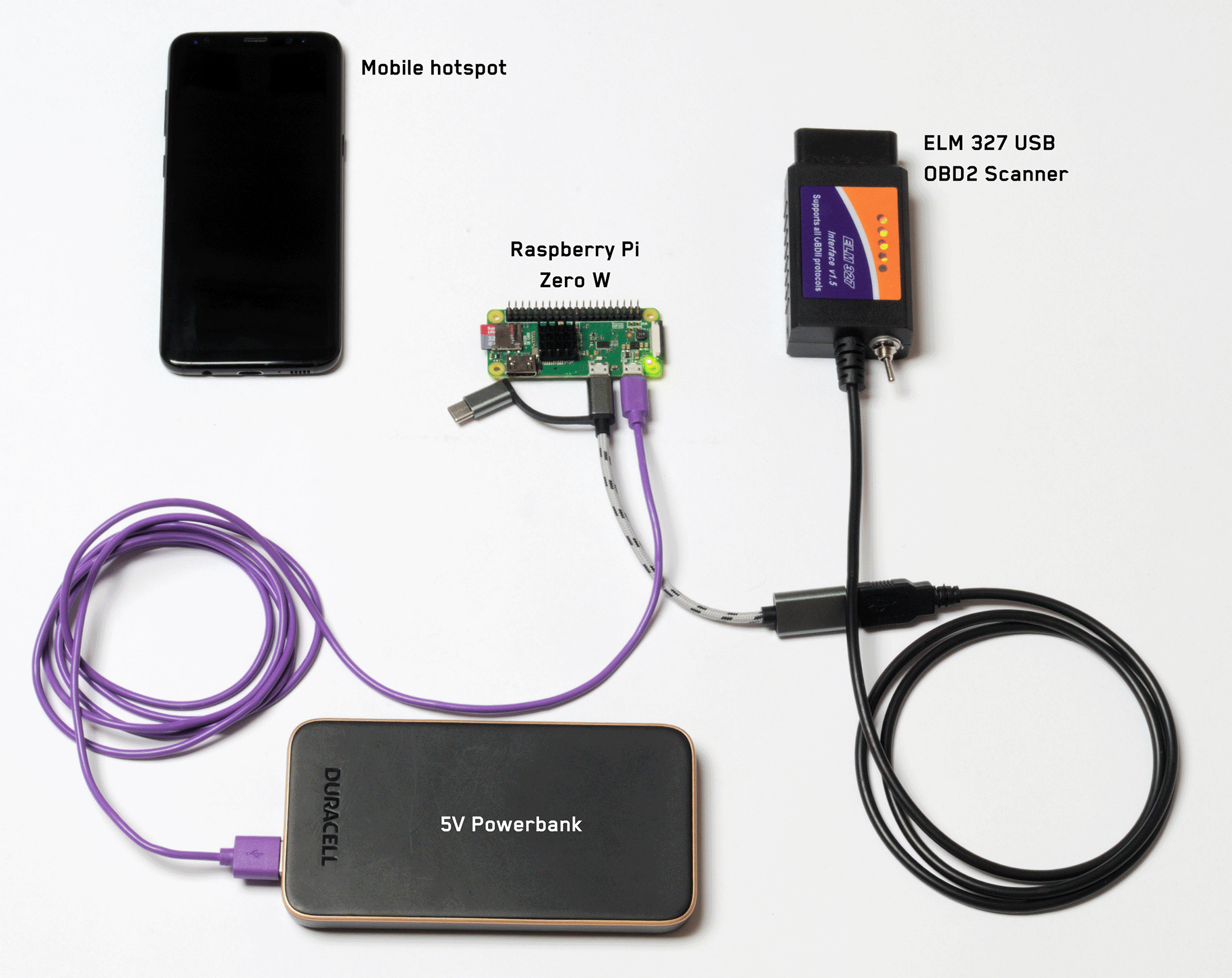

Finally, I would like to draw attention to the use of proprietary technology in these smart home devices. All the devices are equipped with WiFi modules and MCU chips from Tuya. Tuya is a Chinese smart home company that provides technologies to others to facilitate the development of smart home products. This ranges from cloud services, to development tools such as SDKs, to WiFi chips and MCU chips that make it easy to build compatible circuit boards. [13] [14] By offering all these services, it becomes very easy for a third party to develop and distribute smart home products. While this sounds good at first glance, it is a smart move by Tuya to integrate the devices into their ecosystem. This means that all devices are only compatible with the Tuya apps and the Tuya cloud. Therefore, all data collected by the devices is also stored in the Tuya cloud. As the services offered by Tuya are proprietary and not open source in any way, it is not possible to use their service without relying on their cloud.

This is problematic on several levels. On the one hand, companies using their services have to constantly react to changes that Tuya makes to their services without having a say in them. As a customer, this is even more problematic because sensitive data is stored in a cloud that is not under your personal control. As most customers use these devices in a very private space, most likely their homes, this becomes a major risk. Especially since it has already been proven that Tuya stores a lot of information about the devices and their use, such as network status, IP addresses, locations, and even images or videos if the device is equipped with a camera. [14:1] [15]

The second part of this project, is about the attempts to free the devices from the Tuya cloud ecosystem, to gain more control over data usage and to use the devices more freely.

If you have questions, ideas or feedback about this project, I would love to here from you! Feel free to reach out.

In the following the temperature sensors will be referred to with their model number. ↩︎

This forum post was very helpful to identify the components. ↩︎

Prices are from 2023-09-27. ↩︎

https://community.frame.work/t/calculating-the-full-cost-of-a-hardware-product/163 ↩︎

https://www.nextsmartship.com/blog/why-is-aliexpress-so-cheap/ ↩︎

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/special-economic-zones-how-one-city-helped-propel-its-country-s-economic-development/ ↩︎

https://www.china-briefing.com/news/tax-incentives-region-wise-china-comprehensive-summary/ ↩︎

https://www.wired.co.uk/article/dropshipping-instagram-ads ↩︎

https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/handle/2077/52792/gupea_2077_52792_1.pdf;jsessionid=EFF0B3B7B198CE6BED8439FB1559AF6A?sequence=1 ↩︎

https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_voa-news-china_cybersecurity-experts-worried-chinese-firms-control-smart-devices/6209815.html ↩︎ ↩︎