Attaching as Active Practice

An Invitation to Recontextualize RFID Technology in Your Home

When I feel at home, I feel connected. Connected to the space, to the objects filling it, to the people sharing it with me, and, of course, to specific memories. As one changes over time, so does one's perception of what constitutes home. Magdalena Rozenberg describes home as something that is constantly becoming and constantly transforming (Rozenberg 2022). Something that significantly influences our perception of home is the increasing presence of technology.

In this essay, I want to focus on one of these technologies and I invite you, dear reader, to actively engage with this technology and critically question its status quo. The technology I am referring to is probably something you use on a daily basis. It is called RFID, or Radio-Frequency Identification. It belongs to a group of technologies used to attach digital information to our physical surroundings, just as we attach memories to physical things. You probably know it mainly from places outside of what I would consider home. You know it from paying at the supermarket with your phone or your bank card. You use it when a key card gives you access to a specific door. It is embedded in your passport and is hidden in every book that you borrow from the library.

RFID tags are tiny microchips, some no larger than a grain of rice, that blend seamlessly into your everyday environment. (See fig. 1) When a tag comes close to a corresponding device, a current is generated and the read or write operation can be executed. During a read operation, the tag transmits stored information, such as a unique identification number, product details, personal data, or access privileges (Rosol 2017), which have been stored previously via the write operation. In this essay, I will primarily focus on a subtype of RFID known as NFC, or Near Field Communication, which is used in the latest smartphones. Hence, it's highly probable that your smartphone can not only read NFC tags, but can also write to them.

Figure 1: RFID tags in various sizes and shapes © Benno Brucksch 2022

RFID and NFC are also used in what I consider the home, such as home security, home automation, smart appliances, and pet tracking. These uses all share certain principles and goals. Some of them are quite obvious, like the desire for safety and control, and some are rather hidden, like the interests of that companies that sell these products (Fantini van Ditmar 2019). But other principles and goals are also possible. When I explained what NFC and RFID are, I said that they are technologies used to attach digital information to physical surroundings. Let us take a closer look at what is meant here by “attachment.”

“As a thing, ‘attachment’ refers to matters that we add on to something else. Something we connect something else with. … Attachments hold links, connections, details. … Attachments hold a stickiness because they can stick with what they are attached to” (Fjalland 2020, p. 64).

Attaching something to something else is a delicate practice. It can connect what was previously unconnected. As a result, these things are attached. The agents involved in these complex processes can be both human and non-human. Just as a note can be attached to a wall, or a person can be attached to another person or to an object. In her contribution to the book Connectedness - An Incomplete Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene, Emmy Laura Perez Fjalland, a researcher in the field of landscaping practices, points out that, “attachments might then be material, biological, social, cultural [or] organic (to mention just a few)” (2020, p. 64).

I began this essay by explaining what makes me feel at home, namely the attachments I hold. I feel attached to a variety of things, such as certain materials or shapes, as well as intangible things like specific memories. This includes the chair I am sitting on now, which was a gift from my mother, and the postcard I have on my mirror, which reminds me of someone very important. Given the complexity of relationships and the tendency to become attached to things, I propose we conduct an experiment: Attaching NFC tags within the home environment. I invite you to actively participate in this experiment. While the scope of this essay is too limited for a comprehensive technical exploration of NFC, I want to concentrate on enabling you to actively engage with NFC technology:

- As I said, it is very likely that your smartphone is already equipped with NFC. This feature is always enabled on an iPhone, but on phones with a different operating system, like Android, you will need to enable it in the system settings.

- Now, get some NFC tags. I recommend self-adhesive tags from the NTAG family of chips, known for their compatibility and affordability (as low as 15 cents each).

- To get started, download and install one of the many NFC apps available. For example, the free version of NFC Tools is ideal for our purposes.

- Open the app. You will be presented with two options: “read” and “write.”

- If you simply want to add a text record, select “write,” then “add record,” and finally “add text.”

- At this point, enter your desired text and use the “write” option to save it on the tag. Keep in mind that the storage capacity of these tags is quite limited.

- The app will tell you to bring the tag close to the antenna, which, in the case of my iPhone 12, is located at the back upper left corner. On other devices, it may be in the middle of the back.

- To read the text record of the tag, choose the “read” option and again bring the tag close to the antenna.

- You can also store a URL on the tag, which opens up numerous possibilities beyond just a text record. You can use URLs that link to YouTube videos, Spotify songs, or files you stored in the Cloud. If you now choose “add URL,” you can type in the URL and write it on the tag. (See fig 2)

- To read this URL, you now do not need to use the app anymore. Just bring the tag close to the antenna of your phone or any other phone and a notification will automatically pop up. By clicking on this notification, you will be directed to the URL.

Now it is your turn. What are the first things you want to attach together? How about distributing your digital photo or music collection throughout your home? Do you want to reinforce a memory associated with a photo by linking it to a specific song? What kind of connections do you discover through the act of attaching digital content? Does this change anything about your connection to the information or to the objects? And what does all of this do to your perception of home?

Figure 2: An audio tape from my childhood linked to the digital audiobook © Benno Brucksch 2022

Fjalland explains that attachments 'hold a stickiness' and in the case of RFID tags, they conveniently come with a layer of adhesive to facilitate the attachment. When I started using these tags, I began to attach them to various objects around me. I linked digital holiday photos to holiday souvenirs, research papers to my favorite science fiction books, the instruction manual of my synthesizer to the synthesizer itself, music to printed photos, and small web-based games to decorative objects. (See fig. 3-7) I began to link my whole flat with digital content. In my kitchen, I placed tags on the tiles that were linked to different radio stations, and in the hallway, I attached private photos to the walls via tags. Certain connections just made the already existing attachment feel stronger, while other connections established an attachment to a simple object, such as a lighter, that was not there before. As a result, the way I moved around my home and interacted with the objects in it was transformed and became more dynamic. Many things became more exciting to interact with. The act of attaching something digital to a physical object felt like a very strong way of establishing or building something new. The digital and the physical things became part of a new story that was very quickly inscribing itself into my memory.

Figure 3: A handmade fox carved out of wood connected with a self-produced DJ set © Benno Brucksch 2022

Figure 4: The digital version of my master's thesis linked to my personal notebook © Benno Brucksch 2022

Figure 5: More digital photographs of the festival linked to a photograph of the festival gang © Benno Brucksch 2022

Figure 6: The song “Nails, Hair, Hips, Heels” by Todrick Hall attached to my favorite nail polish © Benno Brucksch 2022

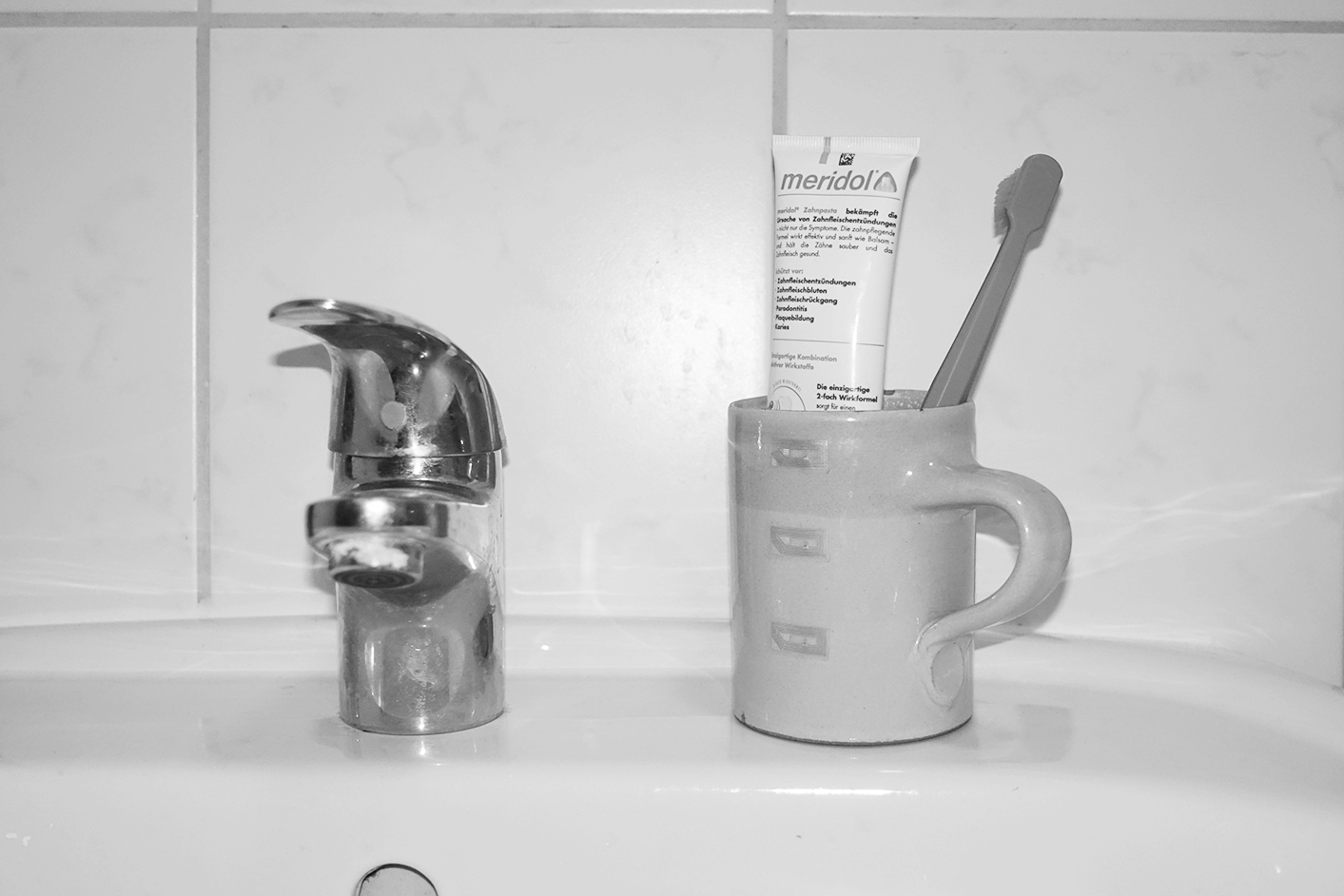

Figure 7: Different songs with a length of 3 min each attached to my toothbrush mug © Benno Brucksch 2022

Technologies have a significant influence on our behavior and on our social relationships – the smartphone is perhaps one of the best examples. The design of new technologies and applications is therefore always an act of (re)shaping these dynamics. RFID is usually embedded so that it is invisible to the user. With this invisibility also comes a position of power, for only a few individuals are able to understand and shape the technology (Hjelm 2005). With the increasing integration of NFC into smartphones, the active engagement of those who carry them in their pockets can serve as an important area for research and the development of alternative ways of uses. To develop such alternatives, there needs to be a democratization of knowledge, skills, and software related to RFID.

The experiments I invited you to take part in do not aim to offer practical, everyday solutions. Instead, they serve as a point of departure for engaging with this technology and exploring the intriguing issues it raises – an approach rooted in my design perspective and my research methods. It is the playful and joyful hands-on engagement that holds the greatest potential for developing one’s own understanding and feeling for RFID and the topic of attachment. My objective in this essay has been to engage you, to encourage you to playfully interact with this technology, to explore its potential uses, and contemplate the implications it holds. The context of the home represents a space where this technology is already being used, but in a very different way. It is a place that already holds many attachments, is very personal to you, and probably also quite different to what I might consider home. Given that RFID technology is already being integrated into many homes and is an important part of future technologies, this essay might be a first step to enable you to actively take part in shaping where this leads us.

References

- Fantini van Ditmar, Delfina. 2019. “The IdIoT in the Smart Home.” In Architecture and the Smart City, ed. Sergio M. Figueiredo, Sukanya Krishnamurthy, and Torsten Schroeder, 1st ed., 157–64. New York: Routledge.

- Fjalland, Emmy Laura Perez. 2020. “Attachment.” In Connectedness: An Incomplete Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene, ed. Marianne Krogh, 64–65. København: Strandberg Publishing.

- Hjelm, Sara Ilstedt. 2005 “Visualizing the Vague: Invisible Computers in Contemporary Design.” In Design Issues 21, no. 2: 71–78.

- Rosol, Christoph. 2017. RFID: Vom Ursprung einer (all)gegenwärtigen Kulturtechnologie. 2., Unveränderte Auflage. Berliner (Programm) einer Medienwissenschaft 7.0, Band 4. Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos.

- Rozenberg, Magdalena. 2023. “The Moving (Rhizomatic) Home.” In Royal Chambers: Home as Host, Host as Home, by Anny Wang and Tim Söderström, 111–17. Stockholm: Arvinius+Orfeus.

Bio

Benno Brucksch (he/him) is a designer, researcher, and lecturer with a focus on digital technologies and their socio-political implications. He studied Industrial Design at Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle (BA.) and COOP Design Research at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation (MSc.). His master’s thesis “Attaching and being Attached,” explores the modalities of RFID technology in the context of personal use by taking a participatory approach. He is part of the Fabmobil team and a founding member of the collective Druckwerk.xyz. Since 2017, he has been a regular lecturer at universities like the Berlin University of the Arts, HyperWerk in Basel, and the University of Art and Design Linz.